Pr. Rasmata Ouédraogo-Traoré in her laboratory at the Charles De Gaulle Pediatric Hospital in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. (Photograph by Serge Ismael Ouédraogo, HID)Rasmata Ouédraogo-Traoré PhD is the Chief of the Medical Analysis Laboratory of the Charles De Gaulle Pediatric Hospital, which houses the National Reference Laboratory for meningitis in Burkina Faso, and a professor of bacteriology-virology, medical sciences and pharmacy at the University of Ouagadougou.

A concerned mother in Burkina Faso says to me, “I think that meningitis is transmitted through eating unripe green mangoes, so I’ve told my children to stop eating green mangoes. Can you confirm this for me?” This is a story many people in Burkina Faso have heard. Although you can’t get meningitis from green mangoes, there is some truth to this anecdote. As scientists, we were able to explain to this woman that it was not the green mango that spreads meningitis, but the time of year when we pick this fruit. During the dry season, also known as “Harmattan,” there is a lot of wind and dust in sub-Saharan Africa. Those conditions, combined with other factors, make for a favorable environment for people to become sick with meningitis.

Meningitis in Burkina Faso

The problem of meningitis in Burkina Faso is a long story. Our country is in the meningitis belt, which is home to a number of African countries with recurrent meningitis epidemics. What still sticks in my mind is the great epidemic we experienced in 1996, when nearly 40,000 cases were recorded and more than 4,000 people died. That epidemic of meningitis was mainly due to serogroup A Neisseria meningitidis for which the population had not been vaccinated. Nowadays, after our country introduced meningococcal serogroup A vaccine, we have seen a reduction in these major epidemics. However, in recent years, there continues to be the threat of meningococcal disease due to other serogroups such as C, W and X. This year our concern has focused on the first outbreak in Burkina Faso due to a strain of serogroup C that previously caused large epidemics in neighboring Niger and Nigeria.

(Photograph by Serge Ismael Ouédraogo, HID)

Excelling in Bacteriology Against All Odds

In the 1980s, I was in my 3rd year of university for pharmacy and took my first bacteriology class, taught by a woman whose extraordinary passion for this subject inspired me toward further study. When our professors only gave us the choice to write our theses about biochemistry, parasitology, or hematology, I successfully petitioned to focus on bacteriology. Following the defense of my thesis, I finished my degree and returned to Burkina Faso where I was assigned to a large referral hospital in the capital Ouagadougou.

“It is my hope that I inspire my students with the same passion for bacteriology that my professor gave to me.”

Upon my arrival, the hospital director initially placed me in the pharmacy department, but I requested to be transferred to the laboratory. Recognizing that I would be the first woman assigned to this laboratory he told me, “I’m sending you there, but I do not want to hear that there are problems between you and the technicians.” Despite early challenges, I never looked back and have continued working as a laboratory scientist. Now as the chief of my own laboratory and a professor at the local university, I work to train and mentor the next generation of Burkinabé bacteriologists. My university bacteriology professor is now retired but I remain in touch with her. It is my hope that I inspire my students with the same passion for bacteriology that my professor gave to me.

The Lab’s Role in Eliminating Epidemic Meningitis

As laboratory scientists, we contribute first to making the diagnosis of meningitis. We base the diagnosis on clinical suspicion, and the role of the laboratory is to confirm or refute this diagnosis. Making an accurate diagnosis contributes to the effective management of diseases. That’s what we do on a daily basis. But, in the context of meningitis epidemics, we are also asked to quickly guide the country as to which pathogen is responsible. This helps inform whether the country should implement a reactive vaccination strategy.

In additional to our role supporting the care of patients, we also support surveillance of bacterial meningitis. Surveillance with strong laboratory capacity allows us to see the disease trends due to individual bacterial meningitis pathogens that are rampant in Burkina Faso. Since 1996, we have seen the laboratory play a very important role. For a given pathogen such as Neisseria meningitidis, five distinct serogroups—A, C, W, Y, and X—cause disease in Burkina Faso. Currently, we only routinely vaccinate to protect individuals for serogroup A, but limited stockpiles of vaccine for other serogroups are available internationally to respond to epidemics.

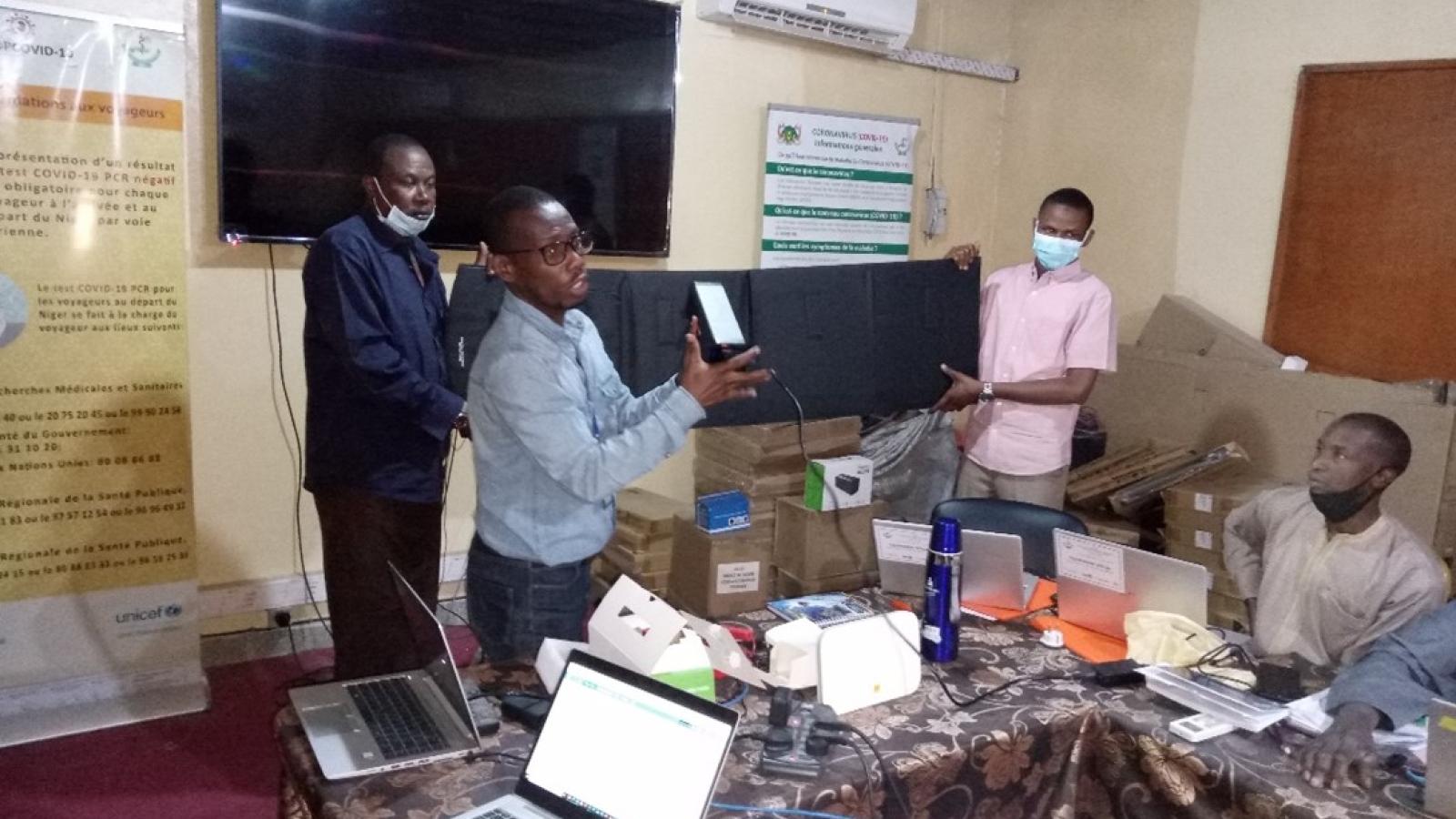

Rasmata with members of her laboratory, R to L : Mamadou Tamboura, Rasmata, Mamadou Baduon and Issa Tonde. (Photograph by Serge Ismael Ouédraogo, HID)

“I am proud of the strong network of laboratories in Burkina Faso that support surveillance and guide epidemic response.”

On the horizon, new vaccines that protect against the other meningococcal serogroups are being developed. If we are able to implement a new vaccine to protect against multiple serogroups using a strategy similar to the meningococcal serogroup A vaccine, I’m hopeful we’ll be able to eliminate epidemic meningitis as a public health concern in Burkina Faso.

Carriage Studies Set the Stage for Future Prevention Strategies

Our country first introduced the meningococcal serogroup A vaccine in 2010. To complement surveillance we’ve been conducting special studies to measure asymptomatic carriage of meningococci to further evaluate this vaccine’s effectiveness. Each round of carriage sampling in the field lasts for four weeks with an additional week of laboratory work to isolate and identify bacteria from the collected samples.

To implement this study we had about 50 people help, including community health workers, chief medical practitioners, samplers, investigators, and laboratory technicians. Even more partners, such as CDC, Norwegian Institute of Public Health and Davycas International, provided technical assistance and helped us with implementation of the study. To date, we have conducted 14 carriage sampling rounds and collected samples from more than 60,000 people! For me, this collaboration is a good example of our strong capacity, leadership, and longstanding international partnerships to successfully implement this critical study.

Health workers take throat swabs for a meningitis carriage study in Noungou, Burkina Faso. (Photograph by Evelyn Hockstein for the CDC Foundation)

The Importance of Good Communication

During a round of our carriage study we had returned to one home in particular to collect samples. A concerned mother in the household asked us about the results of the analyses from the previous sampling—“Is my child sick or well?” I reminded her that our goal was not to diagnose disease but to survey her community to understand better how well the meningococcal A vaccine is preventing transmission. I went on to say “The results of the survey your child and others in this community participated in will be used to ensure the vaccine continues to prevent serogroup A disease.”

Based on my previous experiences with these studies, I believe future studies should focus on communications and awareness. If the population understands the importance of the study, they are more willing to accept and enthusiastically support the ongoing fight against meningitis in our country.

The Future of Meningitis in Burkina Faso

The story about the mother I encountered during the carriage study is an example of the acute awareness and continued burden of meningitis in our country.

“I continue to dream of that day when meningitis epidemics become an old story in Burkina Faso.”

In our communities there is a fear of meningitis epidemics every dry season. Many families have been directly impacted by the disease, and this fear will continue until a new vaccine is available to prevent all epidemic serogroups. In the meantime, through MenAfriNet and other international partnerships we continue to reinforce our surveillance capacity to monitor disease and rapidly confirm the pathogen in our laboratory network. Once a new multi-serogroup vaccine is available, we will be prepared to demonstrate the vaccine’s effectiveness against disease and continue our partnership with our communities to evaluate this new vaccine’s impact on carriage.

I am hopeful that by introducing a new multi-serogroup vaccine in Burkina, we would have taken a very big step toward removing the fear of meningitis in our country, and the communities will feel it because they will no longer experience devastating epidemics. I continue to dream of that day when meningitis epidemics become an old story in Burkina Faso.